John Halstead doesn’t mess around. When he writes, he means business.

Just read his exposition on the most recent explosion of discussion and debate among Pagans and polytheists over superheroes and gods and you’ll know what I mean.

John has a tremendous intellect, and when he writes on Allergic Pagan about the in’s and out’s of theology and praxis he uses that intellect to shed light on the intricacies of what we Pagans, polytheists or non-identified pagan-like-folk do.

When John writes, I listen.

So I took notice when I read the term, “soul-centered” in the list of links at the bottom of his superhero post. I followed the link and found the 3rd of a three-part series from June of 2012 on his evolving sense of Pagan identity entitled, Soul-Centered Paganism.

I read it, and something in me hollered out,

YES!

This.

Work with this.

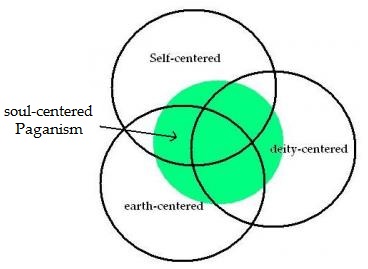

John doesn’t outline a system for what soul-centered Paganism might look like in practice, but he does provide this useful venn diagram. (And don’t we all love those?)

But even without a full breakdown of how soul-centered Paganism might function in practical terms, he does unpack how the term came into existence and how it may be able to connect the earth-centered and Self-centered (or Self-centric) expressions within Paganism:

The writings of Carl Jung, James Hillman, Theodore Roszak (who coined the term “eco-psychology”), and wilderness guide Bill Plotkin, have helped me reconcile these two paths — at least theoretically. From these authors, I have developed a conception of nature and psyche which tries to overcome the dualism inherent in traditional understandings of these concepts.

Conceptually, I understand nature and psyche (or soul) as two different perspectives on the same thing. Step one is to propose that “nature” includes not only our physical bodies, but also that thing which we call mind, including consciousness and the unconscious. That is a proposition, I think, that would be easy for most religious naturalists to accept.

Step two is to reverse the principle: Just as nature extends “within” to include the psyche, so psyche extends “without” to include nature. James Hillman describes psyche (soul), not as something inside of us, but as something that we are “inside” of. Psyche extends beyond our individual mind to include other people and all of nature. Hence, Hillman can speak of “a psyche the size of the earth”.

…

Bill Plotkin calls this ecopsychological perspective a “soul-centered” approach. A “soul-centered” Paganism can potentially combine the earth-centric drive to connect to the more-than-human world with the Self-centric search for greater wholeness, the two being facets of the same drive. From the “soul-centered” perspective, both earth-centered and Self-centered Paganism seek a transcendence of the ego and a transpersonal wholeness.

(emphasis mine)

John, admittedly, doesn’t flush out much of how a deity-centric perspective is factored into it the soul-centered model, but that doesn’t bother me. There’s time for that, I think. What I’m most interested in is the way in which this mediation on perspective (as it relates to the psyche/soul and to nature) brings with it a new, nuanced perspective on the meaning of relationship.

So much of the discussion I’ve seen about “right relationship” with the gods uses the term “relationship” in very much the way that one might speak of a relationship with a human being (or, a being that, while not human, behaves in similar ways that a human might behave). In this way, one “develops relationship,” or “works on their relationship” with the divine. (Some Christians use a similar language when they talk about having a “personal relationship with God.”)

But when you start to wrap your imagination around relationship as something more spacial or dynamic, like the relationship between notes on a scale or frequencies within a spectrum of sound, there is this thing that (at least for me) happens in the mind.

It’s a kind of breaking open.

That and the term, “psyche the size of the earth” — what are the implications of that? Is that not a language of interconnectedness that is worth greater exploration?

John continues that,

Jung wrote that we need to “reconcile ourselves to the mysterious truth that the spirit is the life of the body seen from within, and the body the outward manifestation of the life of the spirit – the two being really one”. I understand “nature” to be psyche seen from without and “psyche” to be nature seen from within. Thus, “nature” is everything inside and out of me when viewed from an objective perspective, whereas “psyche” is everything inside and outside of me when viewed from a subjective perspective.

(emphasis mine)

Again, my brain go break.

For anyone who wants to suggest that the application of one’s intellect necessarily leads one away from spiritual awakening or divine knowledge, I’d have them spend some time in meditation with John’s work. His process is thorough, his conclusions are reasonable, and yet he never makes the mistake of asserting that he has uncovered THE truth about a thing.

His practice is, in part, his process.

As I said, John chose not to articulate how deity-centric thought and practice might intersect with these other two categories for the formation of a soul-centered Paganism. He writes in the comments of his post that

As I was writing though, it did occur to me that all three “centers” are seeking a connection to some form of “otherness”: earth-centered types find this otherness in nature; Self-centered types find it in the deep (personal) psyche; and I think deity-centered types seek it in deities which are conceived as literally other. My problem with the deity-centered approach is that, as I understand it, it places that otherness outside of nature, or at least outside of natural phenomena — which is a problem from my naturalistic perspective — and outside of the Self — which is a problem from my post-Christian perspective.

Must the deity-centered approach place the “otherness” with which we may be seeking a connection outside of nature or the Self? Is there a way to understand or unpack the position of deity as a “natural phenomena” that allows an understanding of the divine that is interwoven with our experience of the soul and nature?

I’m not sure I have the answer to those questions. But for now, I’m borrowing this term, soul-centered, as a way of understanding my own Paganism. Add to that my inclination toward contemplation as a spiritual practice, and I think you may have the making of the “what I am” that I was seeking to identify in my last post.

Leave a Reply