Tag: Religion

-

Caught Up in the Flow: What I Believe

This is less a journal of my proclamations as it is a record of my process. I am figuring it out as I go. If you think you’ve already got it figured out, my writing may likely rub you the wrong way. Over the past several days I’ve been in the midst of what my […]

-

Is Hard Polytheism Incomplete?

I think that hard polytheism is incomplete. I think that there is an underlying unity in all things that hard polytheism — at least, the hard polytheism I see presented most often within my own tradition, ADF — does not take into account. This became clear to me when I began to read Saraswati Rain’s […]

-

Where Does Love Fit into Pagan and Polytheist Traditions?

I am not a Christian, but I have no problem with placing love at the center of my religious ideology. (That I should feel the need to qualify the centrality of love with an “I am not” statement is notable.) When I check in with my desire, my deepest yearning, I discover love. It’s there, […]

-

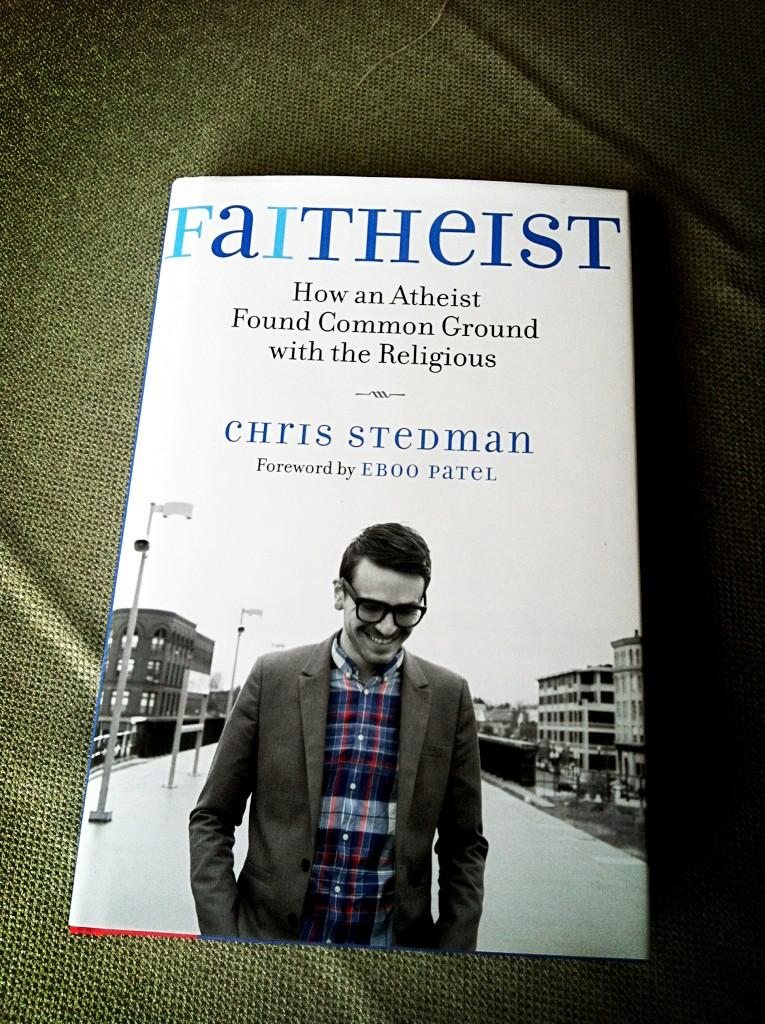

Faitheist: A Quest for Meaning Within Reason

Welcome to the first Bishop In The Grove book club discussion about our February book, Faitheist, by Chris Stedman! Let’s get something out on the table: I have never done a book club before. As such, I’m kind of winging it. My hope is that it can be informal, conversational, and ongoing; I envision there […]

-

Brainstorming and Crowdsourcing a BITG Book Club

I’m starting a book club. The Bishop In The Grove Book Club. Cool, right? For those who are keeping track of the number of projects mounting on my desk, the thought of one more new endeavor probably seems like insanity. But I don’t care. I think a book club sounds like fun. I could use a dose of […]

-

Fragments of a Full Life

I tore it down. I tore it all down. I looked at my space, my little corner room, which is both an office and the home to my small shrine, and I realized that there was something wrong. There was something stale. It did not feel like a sacred space, like an active creative space. […]

-

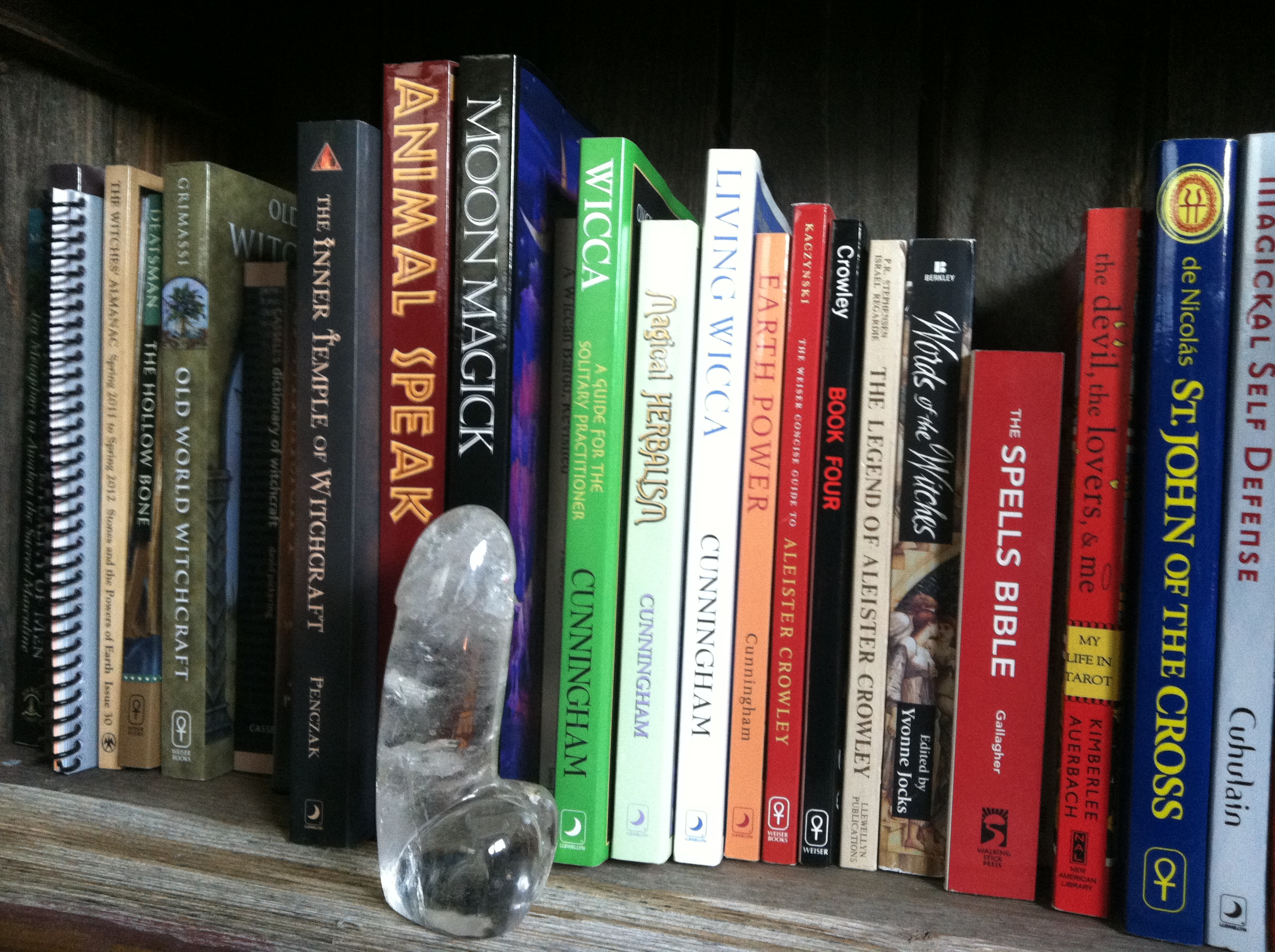

How Much Stuff Does One Pagan Need?

Should I let go of my stuff? Should I have a metaphysical yard sale, in which I sell my Cunningham books, my surplus of pewter jewelry, and my… …ahem… …crystals? Should I rid my closet of the long, green, hooded robe I’ve worn twice, my Guatemalan patchwork jacket I scored for $7 bucks, or my […]

-

Solitaries are the Glue which Hold Paganism Together

I’ve spent nearly the entire week working on new ways to make ADF Druidism an accessible tradition to solitary Pagans. The work is still in its early stages, and I’m piecing together ideas which I hope to share once the leaves have fallen. My backyard maple is only hinting at new color, so it will […]

-

When Jesus Hitches a Ride to the Druid Camp

I’ve been a stay-at-home Pagan, a bookish Pagan, a CUUPS ritual-attending Pagan, and a blogging Pagan. But as of yet, I have not been a festival-going Pagan. That all changes this week. On Wednesday I shall make my way to the Prosser Ranch group campground, located just outside the town of Truckee, California, and celebrate […]

-

Where is the Source of Your Inspiration?

This morning I woke, picked up the pen and paper on the hotel nightstand, and wrote down these words: What is it to write from sleeping? To write without ceasing. To hold back the need to edit, the impulse to correct. The penmanship is awful, but that does not matter. The only impulse is to […]

-

What is the Point of Your Religion?

Last week I asked, “Where does compassion belong among Pagans and Polytheists?” Beneath this first question there is another, more relevant question; one that has been nagging at me for several days: What is the point of your religion? I think this is a valuable inquiry, and no one has asked me this just yet. Yesterday […]

-

Yes, but what do we NEED from our Pagan leaders?

The discussion around the post, What do we want from our Pagan leaders? was enlightening for me. Admittedly, I have a close, personal connection to the subject, as I’m seeking to discover what it might mean that I am, as a friend told me, “called to lead” in some way. This comment really stood out […]

-

Questioning Paganism… Again.

I’m not sure why I’m a Pagan. I type those words, and I know I’m taking a risk by making this admission, but it’s what’s going through my head. My Paganism, as well as my Druidry, is feeling more like subject matter for this blog rather than a way of living my life. Being Pagan […]

-

On Converting a Christian to Paganism

I’m a convert to Paganism. I was born into a Christian tradition, and spent most of the first 25 years of my life identifying as a Christian. I’ve written of this before, but the subject keeps coming up for me. There’s something about how we arrive at our tradition that seems worth reflecting on, especially […]

-

Where Does Belief Belong?

I’m having a difficult time identifying the right place for belief. I was brought up a Christian. Episcopalian, to be specific. Belief, for me, was connected to creeds. If you’ve never recited a creed, it goes like this: I believe X, and X is this. X did this, was this, is going to be this. […]

-

What We Are: One Pagan-American Response

Star Foster asked: “What makes Pagans valuable to America? What do we bring to the table? How do we exemplify American values?”

-

Rules Of Reverence: The Sacred And The Silly

How do we find a balance between our desire for personal freedom and the legitimate need to have a standard measurement in our community?

-

Pill Popping Deities

Are the Gods little more than metaphysical designer drugs for the New Age? Are we in service to them, or is it the other way around?

-

Casting Faith

Pagans are so centered around practice. We define ourselves by what we do, not by what we believe (generally speaking). But faith is all about belief, isn’t it? How do we reframe faith as something that you do instead of something that you have?

-

Imagination is a Pagan Value

Your imagination is where it all takes place. See a deity? Give thanks to your imagination. Create a circle of protection? Again, imagination.